A couple years ago I had read about a new study of the effects from a nuclear power plant exploding in Chernobyl. That has dramatically reduced the amount that I worry about a nuclear attack. There are still effects but they probably will not mean the end of humanity.

Last night I was attempting to explain this to a friend and he was not buying it. Instead he challenged me to do some more research this week on nuclear explosions. I did a search for “Nuclear fallout effects” on my favorite (so far) search engine, Google.

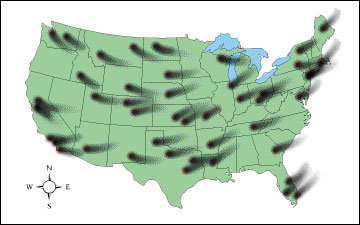

The results are slightly bemusing. We have the effects from atomicarchive.com (that I linked above) which even goes into detail of how the weather and different colored clothing affect the burns you receive during the initial blast. It has a map of the fallout projections from 250 United States cities being attacked:

The discussion last night centered on whether all life on this planet could be destroyed if every existing nuclear warhead were launched. The numbers quoted were in the range of 65-70,000 existing atom bombs.

I don’t believe they would destroy all human life. It would be dramatically changed, but not fully destroyed.

Wikipedia claims that 65,000 nuclear warheads was the peak and that many of those have been partially dismantled (though not destroyed). The Federation of American Scientists claims that there are a little over 23,000 atomic bombs in existence right now. Only ~8,200 of them are operational.

That is still a lot of damage. But there is no way that everyone in every country that has these atomic bombs is going to hit every square foot of land. Even suicide bombers and kamikaze pilots don’t aim for places that have only a single person present. They aim for crowded places or locations with “important” people.

Wouldn’t the nuclear fallout get everyone? Let’s move on down the list of articles from that initial Google search. There was an article from The Straight Dope (you have to like their tagline):

The article ends with a fairly nice explanation of events:

Radiation deaths subsided after seven or eight weeks but latent effects continued to appear for a long time. Fetuses irradiated in the wombs of their mothers were subject to high rates of miscarriage, stillbirth, and birth defects–many kids were retarded or had unusually small heads (microcephaly), stunted growth, or other afflictions. Cases of leukemia surged in 1947 and peaked in the early 1950s. Additional problems included other cancers and blood disorders, cataracts, heavy scarring (keloid), and male sterility. However, no genetic damage was detected in children conceived after the blasts. Oddly enough, notwithstanding all the calamities visited on the Japanese by the bombs, the two things everybody now expects to happen in a nuclear war, mutant kids and the land glowing blue forevermore, didn’t.

Did you catch that? Children conceived after the blast did not have any detectable genetic damage. There were problems with those exposed to the blast itself, even in their mother’s womb, but our bodies are pretty resilient.

Pigs that are released into the wild begin to grow tusks again. Wikipedia says this about “wild boar” (no it was not where I originally learned this):

Wild boars, descended from domesticated pigs, are present in significant numbers in North Eastern Australia. Considered an exotic pest, they are hunted for both sport and population control. They are aggressive and are known to be a vector for tuberculosis.

That is odd from our current outlook on life, isn’t it? Here’s another article from that first search:

http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/health/article1605122.ece

The title is “City air worse than nuclear fallout.” Here’s a quote:

Estimates suggest that a lifelong smoker might on average lose ten years of life because of the habit, while someone who is severely obese (defined as a body mass index score of more than 40) at 35 might lose four to ten years.

By contrast, atomic bomb survivors who were exposed to high levels of radiation within 1,500 metres of the hypocentre of a blast could expect their lives to be shortened by an average of 2.6 years, according to research published online today in the BioMed Central journal Public Health. All of the risks studied showed a similar, relatively small increase (about 1 per cent) in mortality rates among a given population.

Does that put things into perspective? No, I still don’t want to be around nuclear radiation. But perhaps there is hope if nuclear war did break out.